9. What was the original “scientific” name for what we now call AIDS?

Gay-related immune deficiency

The history of HIV/AIDS, even if you just look at Canada, is much more complicated than could be covered fairly in a single blog post. For the purpose of contextualizing this quiz question, I’ll stick to just a few key points.

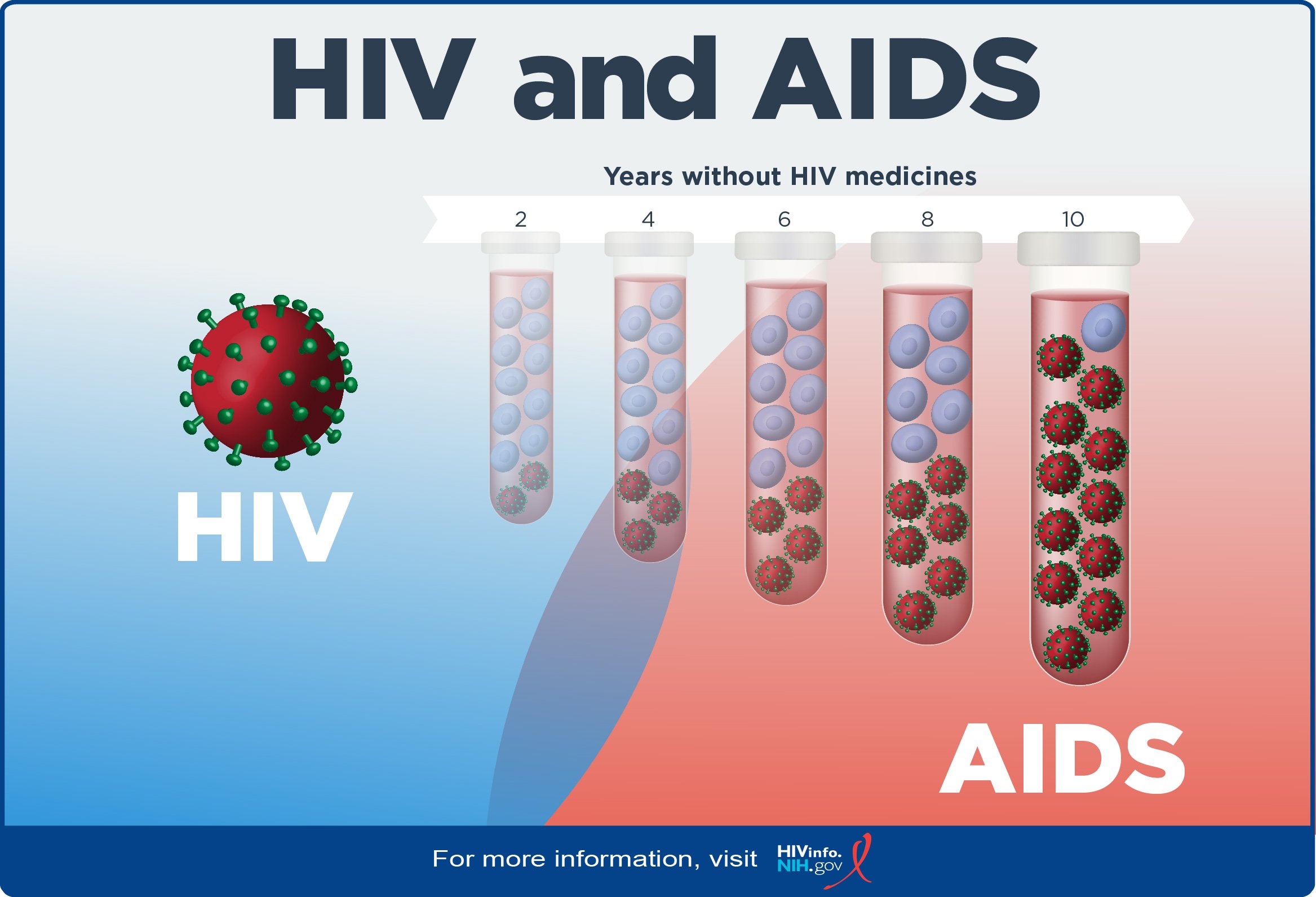

Image: An illustration labelled “HIV and AIDS” showing the progression from HIV to AIDS. On the left, a red ball with many green antennae is labelled ‘HIV’. On the right, a series of five test tubes are numbered 2, 4, 6, 8, 10. The five test tubes are collectively labelled “Years without HIV medicines.” In the left-most test tube, there are ten white blood cells and two HIV molecules. In the remaining test tubes, the proportion of white blood cells to HIV molecules changes, with the HIV molecules replacing the white blood cells. In the right-most test tube, there are eleven HIV molecules and one white-blood cell.

Illustration from U. S. Department of Health and Human Services.

What we now think of as AIDS is a disease of immune system that is caused by the underlying virus of Human Immunodeficiency Virus, or HIV. AIDS is the most advanced stage of HIV, and people who have progressed to this stage of HIV are seriously at risk for opportunistic infections (OIs) that could seriously harm or kill them. We now understand that, without treatment, a person with HIV will usually progress to AIDS over a period of at least 10 years¹—which means tracking the history of HIV and AIDS is very difficult, because the sudden outbreaks of people dying in the 80s and early 90s were almost all people who had been infected at least ten years prior.

Beginning around 1980, doctors in LA and New York noticed outbreaks of two diseases that were uncommon among people who were not known to have compromised immune systems. It was very strange that a sudden rash of cases of Kaposi’s sarcoma, a cancer that caused purple lesions on the arms and face, and an uncommon strain of pneumonia then called pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (also called ‘PCP pneumonia’), were showing up in men who had little in common other than the fact that they were all gay. Suspecting some kind of shared immune condition, the disease (or virus—they weren’t really sure!) was initially called “gay-related immune deficiency,” or GRID. Newspapers and other popular media also called it “gay plague,” “gay syndrome,” and other similar euphemisms ² that sound a little ridiculous to the modern ear.

By the end of 1981, there were published reports of PCP pneumonia among intravenous drug users, and in 1982, three American hemophiliacs (people whose blood does not clot properly on its own) acquired PCP pneumonia after receiving clotting medication derived from human blood donors. It was becoming apparent that the disease did not only affect gay men. The first officially documented case of PCP pneumonia in Canada was published in March of 1982.

Image: a black and white photograph of protestors at the Fifth International AIDS Conference. The protestors are holding signs with slogans like ‘The world is sick… of your quarantines”, “Le monde est tanné … de ta lenteur”, and “SILENCE = DEATH.”

T. L. Litt Photography, “ACT UP storms the stage at The V International AIDS Conference in Montreal.” June 4, 1989.

Despite warnings from international colleagues and the example being set by the American Centre for Disease Control, the Canadian government was slow to respond to the HIV/AIDS crisis. In 1989, Canadians and members of the New York-based group ACT UP stormed the Fifth International AIDS Conference, hosted in Montreal. At the conference, Minister of Health and Welfare Perrin Beatty was forced to admit that there was “no Canadian AIDS plan.” ³ Instead, community groups across the country popped up to take care of their own, and maintain public pressure on officials to take the epidemic seriously.

It wasn’t until 1996 that antiretroviral treatment became available for HIV in Canada. Given advances in treatment, today most people in Canada living with HIV will never progress to AIDS, and can live long lives of similar quality to non-HIV+ people. Given my history working as a sex educator, I can’t end this blogpost without busting a few HIV/AIDS myths:

Although HIV was initially noted in gay men, in 2022 only 34.8% of new cases in Canada were attributed to male-male sexual contact. 39.2% of cases came from heterosexual sexual contact, and 20.5% from injection drug use.⁴ HIV does not discriminate, and if you engage in higher-risk sexual behaviours or use injection drugs, HIV may still be a risk! Read on for more info.

HIV can be transmitted through blood, semen, rectal or vaginal fluid, and breast/chest milk. It cannot be transmitted through things like kissing, sharing drinks, or swimming in the same pool.

People living with HIV who take their ART medications consistently will not transmit HIV. Visit cantpassiton.ca to learn more!

Most people in Canada with HIV will never progress to AIDS, and live long lives of similar quality to non-HIV+ people.

If you engage in higher-risk sexual activity, you can take ART medications to protect against contracting HIV. Check out PrEP and PEP!

For a more detailed timeline about the history of HIV in Canada, see CATIE’s historical timeline.

Further Learning

More photos of ACT UP storming the Fifth International AIDS Conference

HIV Risk Estimator Tool, by the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention

Canada. Commission of Inquiry on the Blood System in Canada. Final Report. Commissioner, Horace Krever. 1997.

Sources/End Notes:

1. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. “The Stages of HIV Infection.” Last updated August 20, 2021. https://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/fact-sheets/stages-hiv-infection

2. Institut Pasteur. 40 Years After the Discovery of HIV Press Kit. Published April 4, 2023. p. 6. https://www.pasteur.fr/en/press-area/press-documents/40-years-after-discovery-hiv

3. Jacalyn Duffin, “AIDS, memory and the history of medicine: musings on the Canadian response.” Genitourin Med. Volume 70, Issue 1: February 1994, p. 65 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8300104/

4. Public Health Agency of Canada, HIV In Canada: 2022 Surveillance Highlights, December 01, 2023. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/diseases-conditions/hiv-2022-surveillance-highlights/hiv-2022-surveillance-highlights.pdf